A Bibliophile’s Bliss

A Bibliophile’s Bliss

In 1971 when Anthony Powell published the tenth volume of his roman fleuve A Dance to the Music of Time he gave it the title Books Do Furnish a Room. Perhaps he was thinking of the library at Tullynally, County Westmeath? After all, Powell was married to Lady Violet Pakenham whose family has been based at Tullynally since the mid-17th century. This has to be one of the most enticing rooms in Ireland, not least because books provide the greater part of its furnishing. Discovering the weighted shelves at Tullynally is akin to attending a party and encountering lots of old friends while being introduced to just as many new ones. (It has to be said the success of this metaphor is assisted by the presence of a drinks table in one corner of the room).

Previously known as Pakenham Hall, Tullynally was deservedly deemed, ‘an early 19th century Gothic Palace,’ by John Betjeman when Britain’s future Poet Laureate stayed there in September 1939. As the late Mark Bence-Jones observed, ‘with its long, picturesque skyline of towers, turrets, battlements and gateways stretching among the trees of its rolling park, Tullynally covers a greater area than any other country house in Ireland’ and looks ‘not so much like a castle as a small fortified town; a Camelot of the Gothic Revival.’ But buried far beneath its romantic carapace of castellations and battlements lies a plain two-storied Georgian house that once served as home to the Pakenham family.

Thomas Pakenham believes the first alterations to the old building were made soon after the marriage of his forebear and namesake Thomas Pakenham to heiress Elizabeth Cuffe; most likely with her money a third storey was added to the house. That earlier Thomas was created Baron Longford in 1756 and almost twenty years later his widow became Countess of Longford in her own right. The second Baron Longford’s accounts record improvements carried out to the building around 1780, mostly raising ceiling heights and altering windows but perhaps more was done since the person responsible for this work was a ‘Mr Myers.’ He could be the Christopher Myers responsible for gothicising Moore Abbey, County Kildare some years earlier.

In any case it was the second Earl of Longford who initiated the real transformation of Tullynally from house to castle. Two of his brothers were professional soldiers and a portrait of one, Major General Sir Edward Pakenham hangs over the polished limestone chimneypiece in the library. He was killed at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815 and for purposes of preservation his body was returned to Ireland in a cask of rum; since he had been known to have a surly temper, one of his relatives laconically remarked, ‘The General has returned home in better spirits than he left.’

Despite his soldier brothers, and his brother-in-law being the first Duke of Wellington, the Earl of Longford seems to have preferred less militant pursuits and carried out extensive improvements on his Irish residence. Between 1801 and 1806 the pre-eminent Irish architect of the period, Francis Johnston worked at Tullynally, adding what one observer has since called ‘little more than a Gothic face-lift for the earlier house,’ notably two round towers projecting from the corners of the main block and battlements around the parapet. In 1817 Lord Longford married and no doubt it was the incentive of a new bride and soon-expanding family that encouraged him a few years later to embark on a second round of work at Tullynally, this time using Johnston’s former clerk, James Shiel. From 1839 to 1842 the third Earl, a bachelor, employed architect Sir Richard Morrison to embellish Tullynally further and to design two castellated wings linking the house with its stable courtyard; a final flourish was added by the fourth Earl in 1860 with the construction of a pinnacled tower at the northern end of the site.

Records show a ‘bookroom’ existed within the house from 1740 onwards, and the first inventory of books there was compiled in 1790, with a second made in the mid-19th century. Thomas once told me he could reconstruct the whole library as it was on either of those dates and compare them with its present holdings. The current contents of 6,000 volumes representing 2,000 titles have been meticulously catalogued across 14 different fields including author, name, subject, language and date of publication.

It comes as no surprise that Tullynally is such a bookish house since the Pakenhams are a dauntingly literary family. Earlier generations might have been renowned for their military prowess but the pen has now decisively vanquished the sword. Thomas’ uncle Edward, sixth Earl of Longford wrote many plays as well as several volumes of poetry. He and his wife Christine (also a playwright) were generous supporters of Dublin’s Gate Theatre from 1930 onwards and later founded the Longford Players. Following his death, he was succeeded by his brother Frank, well-known politician and human rights campaigner as well as author and his wife Elizabeth was an historian. Their children include authors Antonia Fraser and Rachel Billington as well as Thomas who is another distinguished historian but probably now more widely known for his books on trees. Thomas’ wife Valerie has written a number of excellent books and a few years ago their daughter Eliza wrote a history of the Pakenhams in the late 18th/early 19th century.

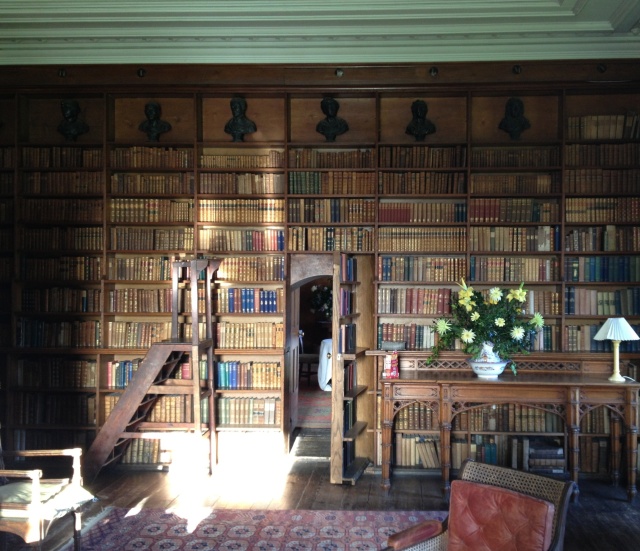

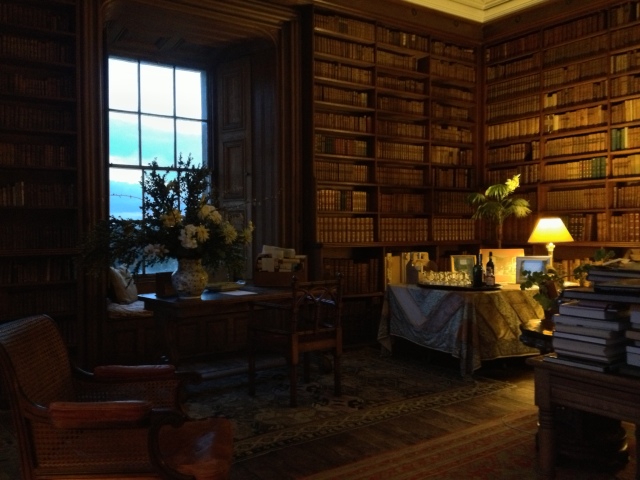

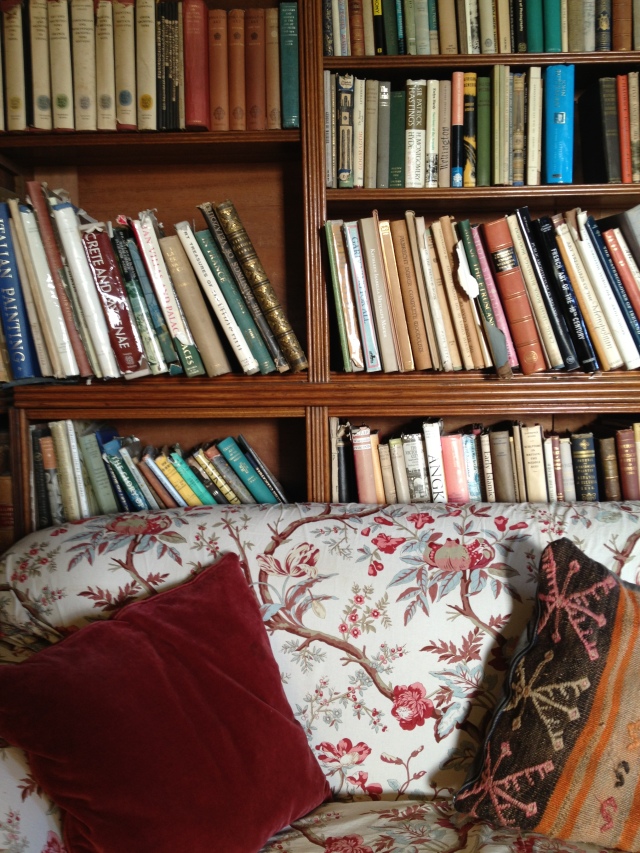

Examples of all their works can be found in Tullynally’s library, the form if not the finish of which dates from the time of Francis Johnston’s intervention. He enlarged the room by stealing a bay from its immediate neighbour so the library now has three south-east facing windows and one facing south-west. It is worth considering what are the elements that make this room aesthetically so satisfying. Obviously its ample proportions help, as does the want of superfluous decoration: the gothic ornamentation found elsewhere is employed very sparingly here. The mellow oak bookshelves covering all four walls and rising from floor to cornice make the greatest impact, especially since most of them carry an amplitude of complementarily-toned leather bindings. Note how the sequence of ten shelves is graduated in height, with smaller volumes occupying the upper levels. The only other feature of note is a set of handsome busts running along the top shelf in one corner of the room. Predating the present library by more than half a century, they represent what were then deemed ancient and modern writers of note. While the library has shutters the absence of poles or even marks in the window embrasures to indicate supports suggests there have never been curtains here. Aside from some Turkey rugs, abundant and comfortable seating, a scattering of mahogany tables and enough lamps to provide light when evening falls, nothing more is required. The library at Tullynally indicates that books do not just furnish a room, they also make it beautiful.

Tullynally’s splendid gardens (and tearoom) are now open and well worth a visit especially since the weather has, at last, improved. For information, see: http://www.tullynallycastle.com

<< Home